After reading Sidney Dekker’s book The Field Guide to Understanding ‘Human Error’, here are some of my emerging reflections and connections. As a consequence of me forming my thinking, this post and its series will likely change over the next few weeks.

A consistent theme throughout the series is the concept of information flow and the safety culture within organisations. Information flow not only impacts physically safety in many industries; it is also an indicator of organisational effectiveness regardless of their industry. As Ron Westrum states, “By examining the culture of information flow, we can get an idea of how well people in the organization are cooperating, and also, how effective their work is likely to be in providing a safe operation.”

Book summary

Based on my notes from the book, here is a summary (aided by Google Gemini)

The “Field Guide” distinguishes between the “Old View” and the “New View” of human error. In the Old View, human errors are the primary cause of problems, and the focus is on controlling people’s behavior through attitudes, posters, and sanctions.

In the New View, human errors are seen as a symptom or consequence of deeper organizational issues, and the focus is on understanding why people behaved in a certain way and improving the conditions in which they work.

The Field Guide provides examples of practices that indicate an organization adheres to the Old View, such as investigations and disciplinary actions being handled by the same department or group, and behavior modification programs being implemented to address human error. These practices tend to suppress the symptoms of human error rather than addressing the root causes.

Information Flow

In this article of the ‘human error’ series, I relate Ron Westrum’s concept of information flow to ‘human error’.

In Ron Westrum’s paper on The Study of information flow, he writes

The important features of good information flow are relevance, timeliness, and clarity. Generative environments are more likely to provide information with these characteristics, since they encourage a “level playing field” and respect for the needs of the information recipient. By contrast, pathological environments, caused by a leader’s desire to see him/herself succeed, often create a “political” environment for information that interferes with good flow.

Westrum, The study of information flow, Safety Science 67 (2014) 58–63

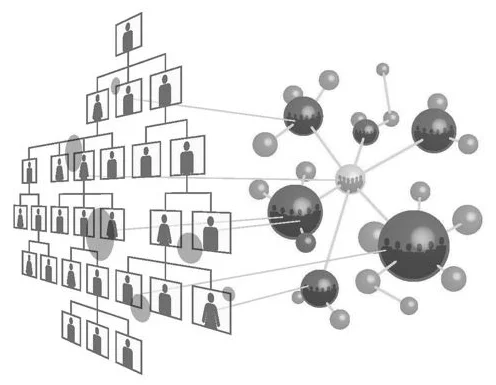

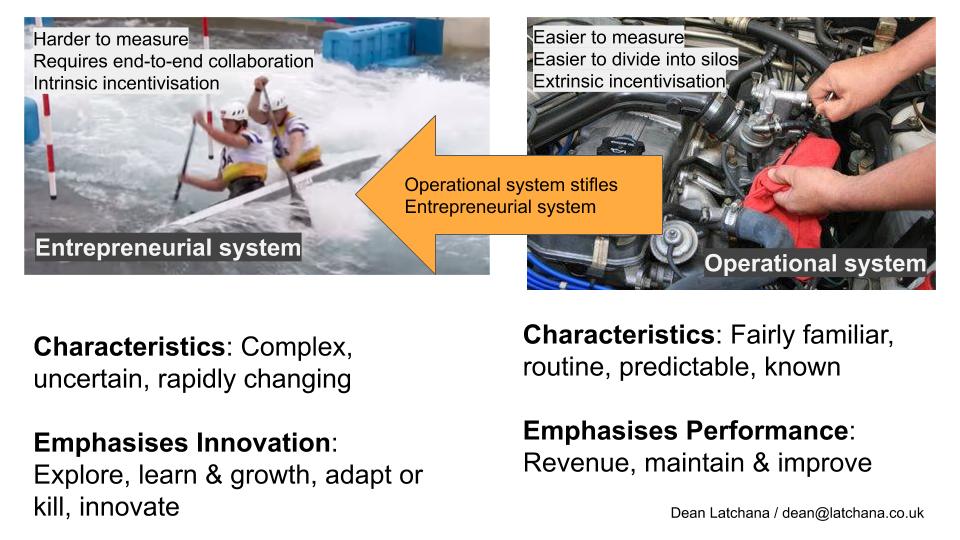

As Westrum describes in his paper, generative environments are those that focus on mission, where everything is subordinated to performance aided by a free flow of information. Pathological environments are characterised by a fear and threat, where individuals hoard information for political reasons.

Between those environments, he identified bureaucratic organisations which tend to retain information within departments for protection.

These cultural styles determine how organisations are likely to respond to ‘human errors’, such as mishaps and mistakes, and to unwelcome surprises such as project-halting issues. In his paper, Westrum sets out ways in which organisations may respond to anomalous information:

- the organization might “shoot the messenger.”

- even if the “messenger” was not executed, his or her information might be isolated.

- even if the message got out, it could still be “put in context” through a “public relations” strategy.

- maybe more serious action could be forestalled if one only fixed the immediately presenting event.

- the organization might react through a “global fix” which would also look for other examples of the same thing.

- the organization might engage in profound inquiry, to fix not only the presenting event, but also its underlying causes.

High performance organisation achieve success with global fixes and inquiry where the ‘bearer of bad news’ is welcomed and supported by their leaders and peers.

Practitioner’s insights

There are means to reasonably approximate where along Westrum continuum an organisation may be. An organisation’s position along the continuum will likely reveal why intractable problems may be nigh on impossible to address.

In my own work, I’ve helped a financial services organisation monitor their position by conducting regular surveys. For the department in focus, individuals at all-levels were asked to rate each of the following kinds of statements:

- Cross-functional collaboration is encouraged and rewarded

- Failures are treated primarily as opportunities to improve the system

- Information is actively sought

- Messengers are not punished when they deliver news of failures or other bad news

- New ideas are welcomed

- Responsibilities are shared

This particular set of statements are from the DORA Research.

To understand the state of information flow within an organisation, practitioners should consider employing the same approach.

Connections with other concepts

Over the next few weeks I’ll be writing this series of posts which makes further connections between aspects of The Field Guide and the following concepts:

- Anti-Fragility, Drift and Resilience

- ‘Human Error’ and Ron Westrum’s Information Flow

- Normalisation of Deviance and the idea of Gradual Acceptance

- Could Wardley mapping be used to map the inattention emergence of drift

- Drift and Cynefin’s zone of complacency

- Roger Martin’s Strategic Choice Cascade

- Hosfstede’s cultural dimensions theory

- Mary Uhl-Bien’s Leading with Complexity