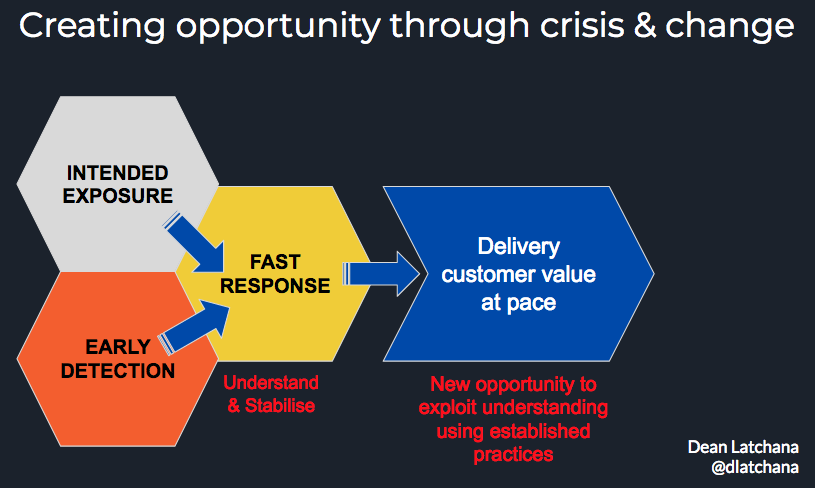

This series of articles examines how organisations can create opportunity following a crisis. I will argue that as the world becomes more complex and undiscernable, how organisations prepare and deal with inevitable failure can give them a competitive advantage. So much so that intentional failure can provide more upside than the downside.

Many readers will be from the fields of Agile and Lean. Following on from my introduction to this series, this article will consider the maturity of these ways of working, but then put them to one-side until the end of this article series.

Why put them to one-side, especially considering I’m an Agile Coach? Well, to be frank, their current application is becoming commoditised. Their essence and original intent are being over-shadowed by large consultancies, large-scale change initiatives, sheep-dip training programmes and certification one-upmanship. Such organisations and initiatives often pay little more than lip-service to Agile’s and Lean’s simple yet powerful approach.

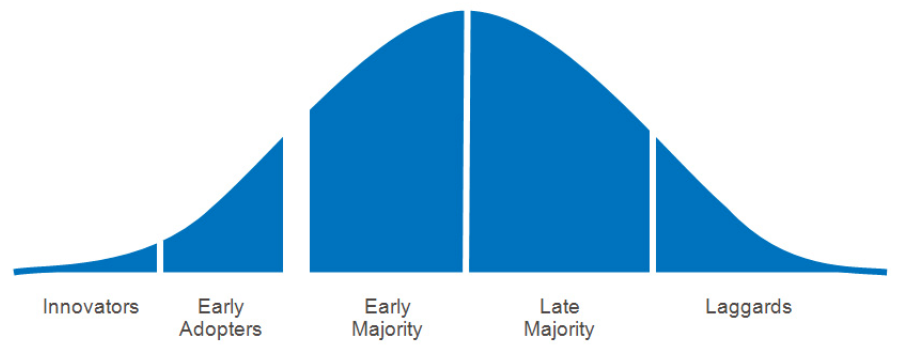

Using Geoffrey Moore’s Adoption Curve, there’s a lot to suggest Agile application is travelling across Early Majority. My opinion isn’t unique; Dave Snowden and many in the agile community recognise this trend.

If we consider ourselves as change-agents, co-developing new emerging ways of working to help our clients and colleagues, we need to look beyond Agile and Lean – particularly in its current commodified application. This is my intent for this series of articles.

Another reason why I shan’t dwell on Agile and Lean is that I believe they have little application during an organisation’s crisis. However, later I will argue they play an important role once a crisis has been stabilised.

There’s a great deal of literature on how Agile and Lean deliver customer value at pace in a complex environment. I’m not going to repeat it here other than to say these approaches are particularly useful when dealing with known problems and opportunities. The challenge is that knowledge and understanding do not exist during shock events and crises that will inevitably engulf an organisation.

Putting Agile and Lean to one-side, in my next article I’ll be returning to organisational resilience. I’ll be telling the story of Nokia, a company that has fallen out of favour yet has an impressive history of resilience.