This series of articles examines how organisations can create opportunity following a crisis and unforeseen change. I will argue that as the world becomes more complex and undiscernable, how organisations prepare and deal with inevitable failure can give them a competitive advantage. So much so that intentional failure can provide more upside than the downside.

In the last article, I explained how, by creating a wide portfolio of business interests, Nokia has remained adaptive to unforeseen change. Having a wide variation allows the organisation to weather the unforeseeable downturn in one area by offsetting it against the unforeseeable rise in another. This ensures survivability and selection.

This article is a case study of how Nokia and Ericsson handled an unforeseen incident differently resulting in the ongoing success of Nokia and the loss of market share for Ericsson.

Diverging fortunes resulting from a 10-minute incident

At the start of the century, Nokia and Ericsson were two dominant mobile phone manufacturers. Both firms were using microchips manufactured by Philips. In the year 2000, a fire in Philips New Mexico factory caused damage to the plant resulting in a halt to the chip supply.

On initial evaluation, Philips assured their customers that production would resume within a week. Nokia was doubtful of Philips assessment and so worked with Philips to find alternatives. They partnered with Philips to find another chipset design to allow manufacturing to continue in other Philips plants.

On the other hand, Ericsson believed Philips assessment that production would be restored within the week. It actually took six weeks. The extended delay caused Ericsson to suffer a critical shortage of chips during a time when handsets were in huge demand. Sales dropped, unused inventory piled up, and their market share declined.

The fire, which took Philips 10 minutes to extinguish, cost Ericsson $200 million in losses in Q2. In contrast, Nokia reported a Q3 profit rise of 42 percent. Ericsson never quite recovered, resulting in Nokia dominating the market for many more years.

Conclusion and the next article

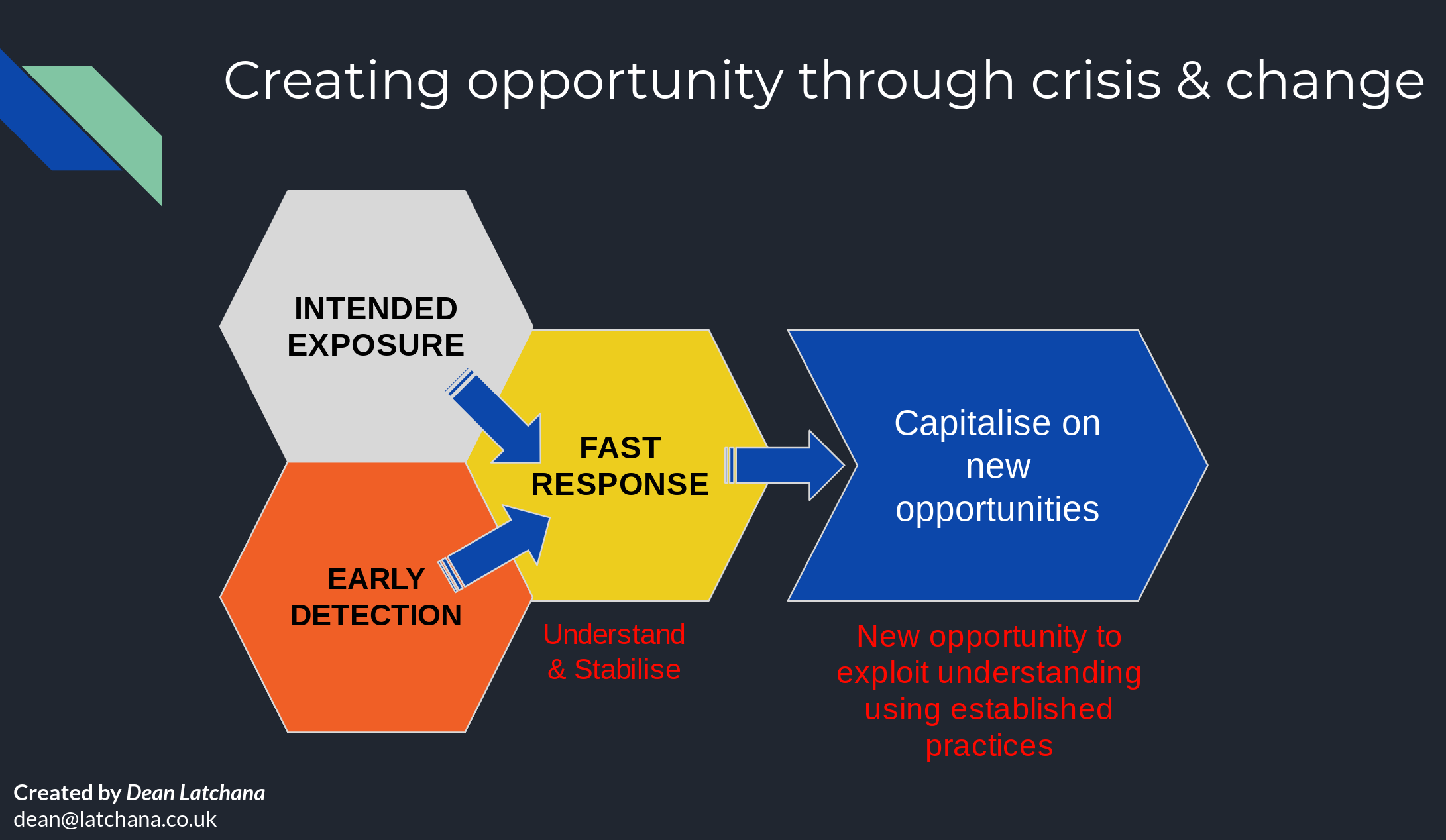

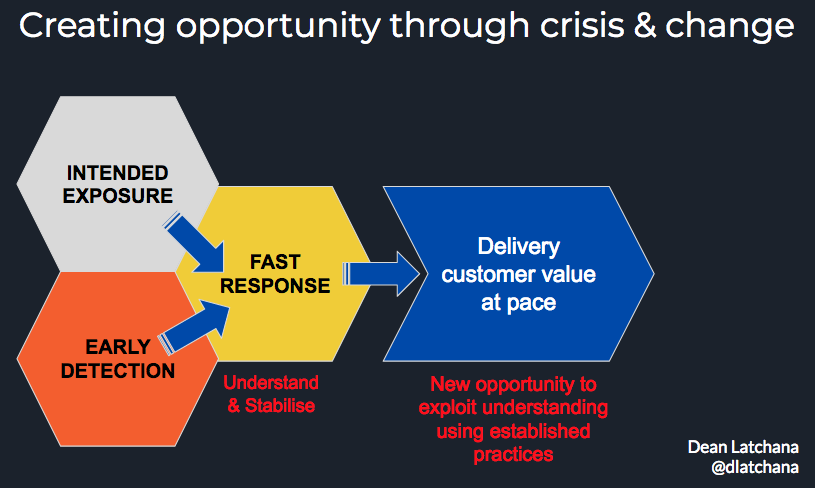

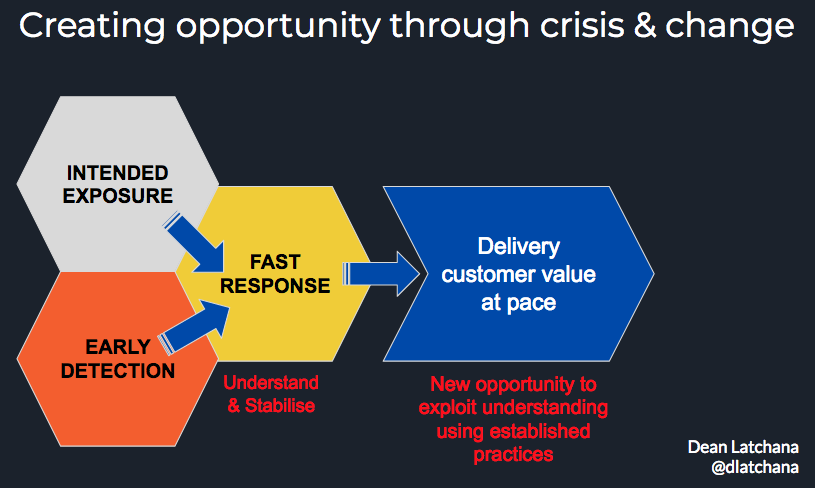

Nokia recognised the fire created vulnerability to its operations and to its market share. It detected the problem early and responded quickly by finding workarounds with their supplier. Ericsson was blind to the threat and lethargic in response.

This capability to detect problems early, and the ability to respond rapidly, enable organisations to be adaptive to unforeseen change and proactively handle crises. To such an extent that they can capitalise on such disruptions to gain an advantage, just like Nokia’s ability to gain market share over its close competitor as a consequence of an unforeseen disruption to their supply chain.

This capability is a demonstration of organisational resilience. It’s a strategic asset that will make or break an organisation.

The concept of resilience is what I’ll be introducing in the next article.

Further reading

You can read more about the Nokia-Ericsson case in Erica Seville’s excellent book Resilient Organizations.

The Economist has written a special report on the incident: When the chain breaks.